Tuesday, March 20, 2007

As a liberal who is strongly and actively opposed to the war in Iraq, I've been challenged many times as to why I didn't serve in the military. Although I've never shared my story before, and it's difficult for me to write this now, it is perhaps the appropriate time. Today marks the 4th anniversary of the start of the Iraq war, and it seems only now are many of the physical and mental costs paid by those who have fought in Iraq becoming apparent to the American people. But all wars extract a similar toll, and my tale is that of the terrible price paid by an American soldier, and his family, in another unnecessary and immoral war a generation ago.

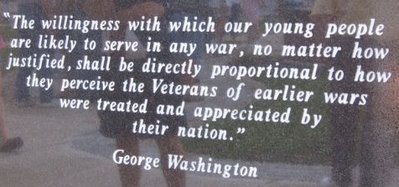

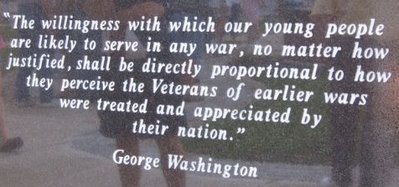

If you've been following the Walter Reed Army Medical Center scandal you've probably seen the following quote by George Washington:

I'm an Army brat. Both my parents were in the military, and my father was a major in the US Army Special Forces, a Green Beret. He served on and off for nearly ten years in Vietnam and Southeast Asia, starting in the late 1950s, and during that time he developed a progressive psychosis that today would probably be diagnosed as PTSD. But back then there was an unwillingness, particularly among elite forces, to accept that combat stress often causes mental illness, and there was a severe stigma attached to any service member who sought or accepted what little treatment was available. Symptoms were often ignored or discounted, and you pretty much just had to deal with it and get better on your own.

Or not. Despite the best efforts of my mother, who spent a couple of years trying to get the Army to recognize that my father was slowly deteriorating mentally, they refused to even evaluate him. My father, of course, denied there was anything wrong, because admitting to it would have ended his beloved military career. As long as he was more or less able to do his job the Army could, and did, pretend that he couldn't possibly be mentally ill, and therefore the problem was really just my mother, who was upset that he was being sent on so many combat tours away from his family.

The result was sadly predictable. When I was eight years old the whole facade crumbled. After a series of increasingly violent incidents involving my father, incidents that were intentionally covered up or minimized by the Army, something finally happened that they couldn't brush aside. First-degree attempted murder, three counts.

My father's intended victims? My mother and two other family members.

The Army, no longer able to deny or hide the fact that my father had become dangerous and unpredictable, took him into custody and then institutionalized him. They finally accepted that my mother had been right all along, but it was far too late for any sort of happy ending. My father's illness was by then so advanced, and he was considered such a threat to medical staff, that the "treatment" they recommended for him was a lobotomy followed by indefinite confinement. Although my mother was able to block the lobotomy, at that time there was very little that could be done to help someone in my father's condition, and he remained institutionalized for many years. Our family was devastated, and I never saw my dad again after his arrest on that winter's night in 1967.

By neglecting to respond to my father's clear symptoms of developing mental illness, and continuing to send him back into combat despite all the warning signs, the Army destroyed a great man. A man who proudly and willingly dedicated his life to serving our country. A man who, in return, deserved not only the appreciation of his county, as Washington said, but also the concern and care that might possibly have prevented his descent into insanity and all the suffering that resulted.

No matter how you feel about the war in Iraq, we have a sacred obligation to care for those we send to fight and die for us. We can afford to lose in Iraq, but we can't afford to let this war break our military. In part because we've succeeded so well in using technology to improve the survival rate of severely wounded soldiers, the single largest cost of this and all future wars will be medical care for soldiers and veterans. If we are not willing to accept and pay that price, and to do whatever is humanly possible to heal our sick and make whole our injured, then we have no right to ask our military men and women to risk their lives on our behalf. And if we ask anyway, the day may come when they no longer answer.

My life has been shaped by the failure of our country to fulfill its responsibility to one particular soldier forty years ago. The personal cost of that failure to my father, my mother, my brothers and sister, and to me, has been quite high. But there was also a cost to our country. A cost that is particularly relevant today as we scrape the bottom of the barrel to find more troops to send to Iraq.

Because of the way I saw my father treated, I did not follow his footsteps into the military, nor did any of my siblings. Our proud heritage as a military family came to an end. Washington's prophetic words, spoken more than two hundred years ago, had proven true.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

More about the quote from George Washington in a later post.

If you've been following the Walter Reed Army Medical Center scandal you've probably seen the following quote by George Washington:

"The willingness with which our young people are likely to serve in any war, no matter how justified, shall be directly proportional to how they perceive the Veterans of earlier wars were treated and appreciated by their nation."Powerful words. They've been engraved on memorials and cited by dozens of veterans groups, members of congress, and US senators, including presidential candidates Barack Obama and John McCain. They have a very personal meaning for me.

I'm an Army brat. Both my parents were in the military, and my father was a major in the US Army Special Forces, a Green Beret. He served on and off for nearly ten years in Vietnam and Southeast Asia, starting in the late 1950s, and during that time he developed a progressive psychosis that today would probably be diagnosed as PTSD. But back then there was an unwillingness, particularly among elite forces, to accept that combat stress often causes mental illness, and there was a severe stigma attached to any service member who sought or accepted what little treatment was available. Symptoms were often ignored or discounted, and you pretty much just had to deal with it and get better on your own.

Or not. Despite the best efforts of my mother, who spent a couple of years trying to get the Army to recognize that my father was slowly deteriorating mentally, they refused to even evaluate him. My father, of course, denied there was anything wrong, because admitting to it would have ended his beloved military career. As long as he was more or less able to do his job the Army could, and did, pretend that he couldn't possibly be mentally ill, and therefore the problem was really just my mother, who was upset that he was being sent on so many combat tours away from his family.

The result was sadly predictable. When I was eight years old the whole facade crumbled. After a series of increasingly violent incidents involving my father, incidents that were intentionally covered up or minimized by the Army, something finally happened that they couldn't brush aside. First-degree attempted murder, three counts.

My father's intended victims? My mother and two other family members.

The Army, no longer able to deny or hide the fact that my father had become dangerous and unpredictable, took him into custody and then institutionalized him. They finally accepted that my mother had been right all along, but it was far too late for any sort of happy ending. My father's illness was by then so advanced, and he was considered such a threat to medical staff, that the "treatment" they recommended for him was a lobotomy followed by indefinite confinement. Although my mother was able to block the lobotomy, at that time there was very little that could be done to help someone in my father's condition, and he remained institutionalized for many years. Our family was devastated, and I never saw my dad again after his arrest on that winter's night in 1967.

By neglecting to respond to my father's clear symptoms of developing mental illness, and continuing to send him back into combat despite all the warning signs, the Army destroyed a great man. A man who proudly and willingly dedicated his life to serving our country. A man who, in return, deserved not only the appreciation of his county, as Washington said, but also the concern and care that might possibly have prevented his descent into insanity and all the suffering that resulted.

No matter how you feel about the war in Iraq, we have a sacred obligation to care for those we send to fight and die for us. We can afford to lose in Iraq, but we can't afford to let this war break our military. In part because we've succeeded so well in using technology to improve the survival rate of severely wounded soldiers, the single largest cost of this and all future wars will be medical care for soldiers and veterans. If we are not willing to accept and pay that price, and to do whatever is humanly possible to heal our sick and make whole our injured, then we have no right to ask our military men and women to risk their lives on our behalf. And if we ask anyway, the day may come when they no longer answer.

My life has been shaped by the failure of our country to fulfill its responsibility to one particular soldier forty years ago. The personal cost of that failure to my father, my mother, my brothers and sister, and to me, has been quite high. But there was also a cost to our country. A cost that is particularly relevant today as we scrape the bottom of the barrel to find more troops to send to Iraq.

Because of the way I saw my father treated, I did not follow his footsteps into the military, nor did any of my siblings. Our proud heritage as a military family came to an end. Washington's prophetic words, spoken more than two hundred years ago, had proven true.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

More about the quote from George Washington in a later post.

No comments:

Post a Comment