Washington is losing its sway over Southeast Asia as its chief competitor China emerges as a global power with a diplomatically attractive no-strings-attached policy on aid and investment. As US hegemony gradually comes to an end, so too it seems will the region's short-lived experiments with democracy and financial liberalism.ASIA HAND

US, China square off

By Shawn W Crispin

BANGKOK - Of all the factors that contributed to Thailand's mid-December decision to impose restrictive controls on short-term capital flows, which subsequently flattened the stock market and sparked howls of discontent from foreign investors, Thai authorities' primary motivation for the fateful policy was left unnamed, but clearly it was China rather than the US.

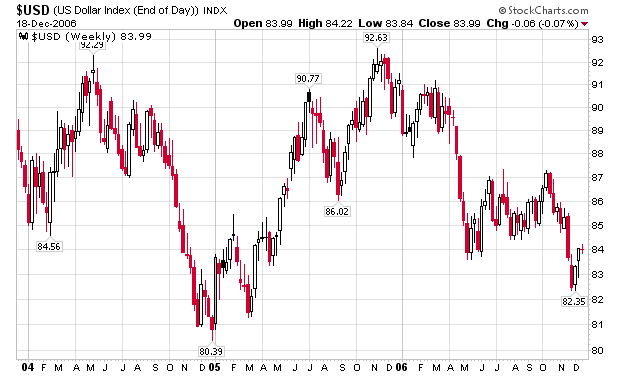

The rapid appreciation of the free-floating Thai baht against the fixed-rate Chinese yuan rather than the US dollar had in recent months severely eroded Thailand's overall export competitiveness, particularly in the crucial electronics sector, which accounts for about 35% of Thai exports. If the baht-yuan gap had widened further, Thai central bank authorities feared that a stronger baht would have bankrupted its exporters and severely crimped economic growth.

It's not the first time that China's rigid exchange-rate policy has sent ripples of financial instability through Southeast Asia. In retrospect, some economists believe that Beijing's decision in 1994 to peg the yuan to the US dollar at the artificially low rate of 8.2 per greenback was a crucial determining factor in the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, which devastated the region's currencies, bourses, banks and broad economies.

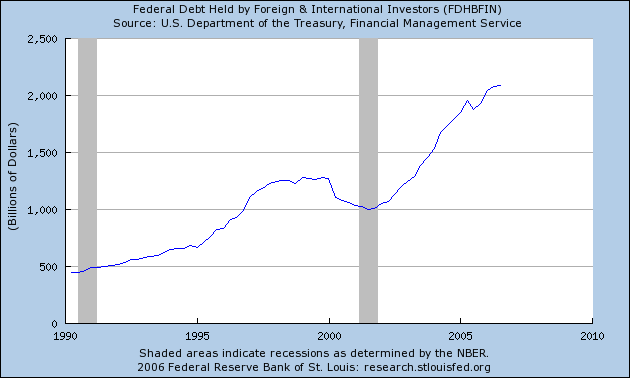

The move to a pegged rate facilitated China's emergence as a global economic powerhouse, in many respects at the expense of Southeast Asia's financially crippled export-driven economies. Then, Beijing extended a symbolic US$1 billion to the region's suddenly debt-ridden governments. Since, Beijing has launched an economic charm offensive across the region, facilitating trade and investment linkages for regional countries to share in the Middle Kingdom's explosive growth.

China has firmly emerged as an important new destination for the region's natural-resource exports, a supplier of cheap goods and services and, increasingly, a source of badly needed foreign direct investment. Southeast Asia's growing economic reorientation toward China is expected to accelerate into 2007, as the United States' appetite for the region's exports tapers off because of slowing economic growth.

Geographical pull means Southeast Asia will increasingly look toward its giant northern neighbor for new trade and investment opportunities, a trend that should accelerate as regional business seeks ways to make up for lost sales to the US. That's already happening: Sino-Southeast Asia trade surged to $130 billion in 2005 and is on pace to grow even faster this year. The two sides are now negotiating a free-trade agreement that would potentially form the world's largest free-trade area in the world by 2010.

Double-edged sword

But China's economic advance into Southeast Asia has not been a strictly benign phenomenon, as frequently characterized by Chinese officials upon the announcement of "mutually beneficial" trade, investment and aid pacts. Thailand's recent drastic reaction to China's pegged exchange rate tells a significantly different story, one that threatens to undermine the region's broad post-1997 trend toward more financial openness, particularly in export-oriented economies in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines that, like Thailand, are seeing their exports squeezed by an appreciating exchange rate vis-a-vis the Chinese yuan.

Moreover, Chinese aid and investment, while stimulating much-needed economic growth, has also helped to prop up some of the region's more authoritarian regimes, including those in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. With China's rise, Southeast Asian governments are increasingly able to pick and choose between economic engagement with either the US or China, and many are opting to open their economies to Beijing because Chinese capital comes without the political baggage of US finger-wagging about the need to move towards more democracy and universal economic openness.

China's fast rise and the United States' slow fade from Southeast Asia is unmistakably undermining the region's often tumultuous but at the same time highly important experiments with democracy, economic openness and financial liberalism. This represents a significant course shift, one that threatens to undermine the region's once bold, now fading, democratic aspirations.

During the Cold War, when the US, Europe and Japan fueled the region's rapid economic growth through free trade and manufacturing-oriented investments, the economic privileges were often predicated on a loose understanding that recipient countries would move toward more liberal democracy and economic openness - a policy that in retrospect worked to varying degrees of success.

When the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis broke out, the US-influenced International Monetary Fund predicated its multibillion-dollar bailout packages on a commitment to more, not less, economic and financial openness. That strings-attached counsel included the abandonment of the region's fixed-exchange-rate regimes for free-floating ones, and the subsequent market-driven devaluations helped to spark the region's exports and economic recoveries.

At the same time, Washington often scolded and in some egregious cases even imposed sanctions on Southeast Asian countries for their poor rights records, including an arms embargo on longtime ally Indonesia over military-related abuses in East Timor, and full-blown trade and investment sanctions against oil-and-gas-rich Myanmar related to its long-standing abysmal rights record.

Bygone moral era

Those demands and sanctions, however, hark to an arguably bygone era when the US was widely perceived in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in Asia as a moral force for democratic change. The George W Bush administration's recent policy emphasis on regional cooperation for its counter-terrorism campaign, and its attendant restrictions on civil liberties, including the implementation of anti-terror codes allowing for detention without trial, policies the US previously scolded in the region, has badly eroded the United States' stature here.

Moreover, Beijing's mix of political repression and economic success has sent a bold new message to the region's leaders that democracy and financial openness are not necessarily preconditions for economic prosperity. China's various anti-democratic policies, from its brutal crackdowns on free speech and political dissent, to its sophisticated control and censorship of the Internet, to its outrageous official land grabs from urban squatters and rural peasants, are gaining currency across Southeast Asian countries that increasingly see China as a development role model.

Worryingly, that trend is taking hold not only in Southeast Asia's underdeveloped but emerging economies, but is also prompting anti-liberal backtracking in the region's more established economies, including Thailand and the Philippines.

Consider the US-versus-China contest now under way for influence in Cambodia. In recent years, Phnom Penh has relied heavily on Western donors for its economic sustenance, including aid that accounted for more than 60% of the government's annual budget. To sustain that Western aid, the Cambodian government was required to move toward more democracy and economic openness - a policy that was arguably successful by half.

When Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen jailed a journalist in 2005 for his critical reporting, the authoritarian premier was forced to back down and release the scribe by US and Western pressure. Hun Sen was also apparently persuaded by the US and European countries to amend Cambodia's criminal-defamation codes and eliminated jail terms as a possible penalty for libel.

Enter China into the mix: in April, Beijing extended $600 million worth of no-strings-attached foreign aid, on par with the Western-led Consultative Group's contingency-laden $601 million. Since, Hun Sen's government has resumed jailing critical journalists on so-called "disinformation" charges, a popular tactic Beijing uses against Chinese journalists. And there are growing indications that the government is trying to wiggle out of its commitment to a United Nations-backed tribunal for former Khmer Rouge leaders which promises to unearth details of China's past support for the murderous Maoist regime.

Myanmar represents another case in point. Myanmar's ruling junta for years teetered on the brink of financial collapse under US-led economic and investment sanctions, imposed for the military regime's abysmal rights record. Beijing sometimes provided a helping hand when finances were particularly tight, including in the wake of the 1997-98 regional financial crisis, but Myanmar's sorry financial state then reflected the still-tentative state of China's own national finances.

Now, Myanmar's generals are swimming in cash and politically secure as an economically empowered China invests heavily in the country's untapped oil, gas and hydropower resources. China provided crucial funds to finance the junta's bizarre and expensive 2005 move of the national capital from coastal Yangon to inland Naypyidaw, a move apparently motivated by the junta's peculiar fears of a possible US-led preemptive invasion.

Abandoned high ground

As China gains more economic and political influence in Southeast Asia's less developed peripheral states, the US is increasingly abandoning the democratic high ground and subordinating its regional diplomacy to plain economic and strategic interests - that is, the US is contesting the region on China's terms, not its own.

That was plain in the recent trade deal the US brokered with Vietnam - a country that both Washington and Beijing are bidding to sway into their diplomatic orbit. Earlier, the US had pushed Hanoi to improve its abysmal religious- and human-rights record substantially before the US would back its bid to accede to the World Trade Organization. In November, Bush blatantly backtracked on that requirement and endorsed Vietnam's membership to the world trade body even as the communist regime brutally cracked down on the country's nascent pro-democracy movement, including while Bush was attending the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting held in Hanoi.

Even where US interests are firmly entrenched, China's growing influence is altering the United States' diplomatic calculus, prompting it to drop democracy promotion from its policy priorities toward the region.

In November 2005, the US dropped an arms embargo it had maintained against the Indonesian military after it went on a death and destruction rampage in the wake of East Timor's 1999 vote for independence. The flip-flop came soon after China extended $300 million in credits for Indonesian infrastructure projects and more than $10 billion more in private-sector investments. The policy U-turn also notably came at a time the Indonesian military was coming under new fire from international rights groups for alleged human-rights abuses in Papua province - where the Indonesian government tellingly bans foreigners from traveling.

Similarly, Washington repealed about $14 million in military aid to Thailand in the wake of the September 19 military coup that abolished the progressive 1997 constitution and ousted democratically elected prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra - who coincidentally was viewed in Washington as moving its erstwhile strategic ally in the region closer to China.

Tellingly, in the wake of the coup the US quietly maintained aid earmarked for Thai-US anti-terrorism cooperation, including funds for the Bangkok-based Central Intelligence Agency-led Counter-Terrorism Intelligence Center, which apparently played a role in establishing the secret prison Thailand hosted for the US to interrogate regional terror suspects, as first reported in the Washington Post.

Concerned that the US might lose a step to China - which significantly remained mum on the military coup - US Ambassador to Thailand Skip Boyce in a meeting directly after the coup reassured the country's new military leaders that Washington was obliged by law to sanction the military intervention and that bilateral relations would stay on track despite the Thai junta's suspension of civil liberties, according to a senior Thai official.

Even in the Philippines, where the US has now stationed troops to help the Philippine armed forces flush out Muslim insurgent groups that Washington believes have links to international terror groups, China is making distinct economic inroads. In September, China announced its intention to extend $2 billion in loans to the Philippines, a generous offer that dwarfed the $200 million the US-influenced World Bank and Asian Development Bank tabled. Moreover, Beijing's backing to a an official Code of Conduct for the South China Sea helped to ease Philippine concerns about the two countries' longtime competing claims to the Spratly Islands.

Shifting strategic calculus

China's economic diplomacy is in effect easing Southeast Asia's historical skittishness about Beijing's long-term intentions toward the contiguous region. In turn, that's slowly but surely starting to erode the United States' rationale for maintaining and expanding a strong strategic position in the region, and is in effect undermining Washington's apparent designs to fragment the region into competitive pro-US and pro-China camps. To be sure, certain regional countries such as Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia remain wary of China's growing strategic clout and still favor a counterbalancing US presence.

Yet the US is tellingly having a tougher time selling new strategic regional overtures, because of a growing number of countries' concerns that overtly siding with the US could irk China, which has long feared US strategic designs of encircling its porous southern periphery. In July, landlocked and impoverished Laos rebuffed a US offer to send military engineers to help build schools, clinics and roads. Laotian Defense Minister Major-General Duangchay Phichit said his country would welcome US funds, but not US troops on Laotian soil.

More significant, Vietnam, which fought a border war with China in 1979, has reacted coolly to recent US overtures to gain access to military port and airport facilities at Cam Ranh Bay because of its concerns about how China might react. And strategic analysts say Indonesia's recent decision to purchase as much as $3 billion worth of Russian rather than US armaments was partially made to allay Beijing's concerns about US-Indonesian military interoperability during a potential US-China conflict where the US might attempt to block the nearby Malacca Strait, through which about 80% of China's imported oil currently flows.

All this means that the US has lost a significant step to China - economically, politically, and strategically - in Southeast Asia's increasingly important strategic theater. All indications are that the region is moving toward more Chinese and less US influence, and as US hegemony gradually comes to an end, so too it seems are Southeast Asia's short-lived experiments with democracy and financial liberalism.

Shawn W Crispin is Asia Times Online's Southeast Asia editor.

Copyright 2006 Asia Times Online Ltd.