By Bonddad

One of the main reasons I have focused a great deal of attention on housing is its primary role in the current US expansion. From jobs to consumer spending money, housing have been the driver. Below I will explain how this works.

These paragraphs are from an interview in Barron's with Bennett Goodspeed of Inferential Focus (subscription required):

We've been talking about housing for 2½ years. The anomaly of the 2001-2002 recession following the dot-com blowup was that consumer spending never slowed down and personal debt never slowed down. At the same time, real incomes were not increasing. It was the first time in decades where there were five years straight in which real incomes did not increase. Cash-out refinancing and home equity loans filled the gap. This is the first time in the postwar period that the housing market has fueled the economy. It has regularly gone through the cycles with the economy, but it hasn't ever fueled the economy and supported consumer spending. A lot can ripple out from the housing market. We're seeing the first wave. We are suggesting to clients that corporate reactions to protecting earnings might be a hidden factor that could lead to other shock waves involving housing.

Corporate managements have been so well-trained to cut back on expenses to protect earnings that it might be the catalyst that trips the next wave. There's been a huge increase in housing supply on the market, turnover is way down, but prices have plateaued after going down a slight amount. That's because we haven't had any forced sales. If there are corporate layoffs, there will be forced sales. There has been a lot of leverage created in the housing market and it could lead to a significant decline. About 40% of the new jobs in the last four years are housing-related. Housing is 23% of the overall economy. While there are offsets -- commercial real estate is doing well and the government is hiring -- this has the potential to tip the scales. It could lead to the Fed lowering rates, and if we've got to lower interest rates to stimulate the economy, it takes the incentive out of owning dollars. That becomes tricky when you consider it's important for the Chinese to help support our economy by continuing to buy dollars.

In the first paragraph Goodspeed is talking about the relation between incomes, consumer spending and household debt. What he's basically saying is incomes didn't increase for a few years but consumer spending continued to increase. That means the money for consumer spending had to come from somewhere, and housing provided the funds in the form of home equity withdrawal (HEW).

Let's coordinate several pieces of data to see what Goodspeed in talking about. (This information is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics). In November 2001, the average hourly earnings of production workers was $14.74. This number was $17.22 in March 2006 for an increase of 16.82%. Over the same time, the inflation gauge increased from 177.4 to 205.352 for an increase of 15.756%. That means for the duration of this expansion, wages have increased 1.06%.

At the same same time consumer spending has continued unabated. Personal consumption expenditures were $7.188 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2001 and $9.589 trillion in the first quarter of 2007 for an increase of 33.4%. Using the inflation number from above (15.75%) we get an increase of 17.65% in consumer spending. Yet, wages only increased 1.06%. Where did the extra money come from?

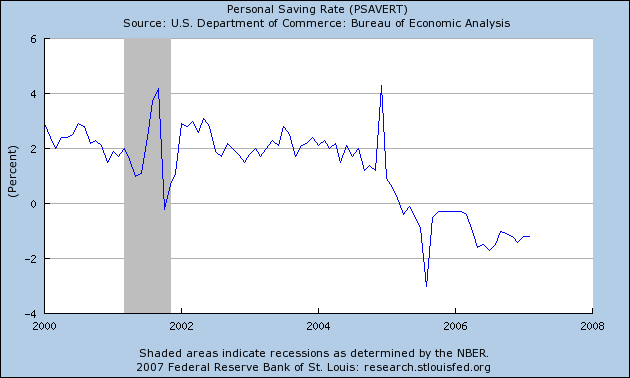

It wasn't from savings. The US savings rate was about 2% of disposable income in November 2001 and has been negative for the last 8 quarters. That means consumers have been dipping into savings to pay for their expenditures. However, the decrease in savings isn't enough to make-up for the increase in consumer spending. Here's a chart.

So let's review. Wages haven't increased much beyond inflation for the duration of this expansion. Yet consumer spending has increased. But consumers aren't dipping into their savings. Where is this extra-money for consumption coming from?

Debt. According to the Federal Reserve's Flow of Funds Report household debt (mortgage + credit card debt) has increased in a big way during this expansion. In 2000, household debt was 97% of disposable income; at the end of 2006 it was over 130%. over the same period, household debt increased from 74% of GDP to over 90% of GDP.

Let's look at jobs.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there total private employment was 130,883,000 in November 2001 and 137,622,000 in the latest survey. That's a total gain of 6,739,000. over the same period, construction employment was increased from 6,784,000 to 7,713,000 for a gain of 929,000. The BLS classifies real estate jobs under financial services, which increased from 7,845,000 to 8,451,000 over the same period. About 20% of these jobs are real estate related, or 121,000. In addition, over the same period professional services increased from 16,094,000 to 17,829,000 or a gain of 1,735,000. Let's assume that 20% of these are in some way related to real estate (appraisers, architects, lawyers etc..), which is 279,400 jobs. Adding these rough estimates, we get 1,329,000 jobs, or about 20% of the total jobs created. It's important to remember that Goodspeed has a group of talented number-crunchers on his staff who have access to far more detailed information. In other words, comparing his methods to my rough guestimates, I'd be inclined to take his analysis over mine. However, regardless of who's right, even 20% of total jobs is a ton of jobs created by a single industry. The point of all of this is simple: housing has created a ton of jobs in this economy.

SO, as a source of funds to fuel spending and as a driver of employment gains, housing is very important. So far we've seen the housing slowdown hit GDP for 4 quarters in a row. There hasn't been a big hit to employment yet. But with the slowdown in home construction, I wouldn't count on that lasting.

For economic commentary and analysis, go to the Bonddad Blog

No comments:

Post a Comment